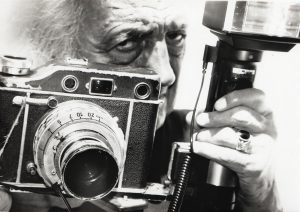

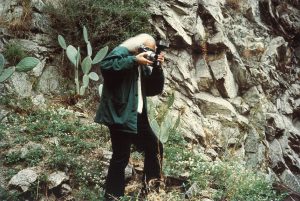

Giacomelli developed his photographic technique in order to actualise his notion of his camera as one of his own limbs (as he terms it: ‘an extension of my idea’). Giacomelli’s creative approach maps out “escape routes away from convention.” He pushed his camera to its extremes, modifying it to fit his precise needs, and abusing it. His camera became a means of deconstructing reality, or rather deconstructing the common conception of reality as static.

Giacomelli’s oeuvre is a system of continual mutations; it is a whole consisting of interrelated parts; a living organism. Each series is not a closed chapter. Giacomelli continually redefined his photographic series by returning to certain images like snippets from past conversations. He revitalised them by setting them in new contexts, seeking to ‘breathe life into things via the pretext of Photography.’

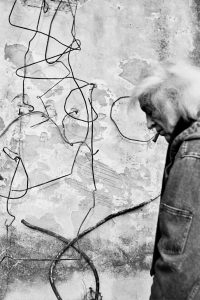

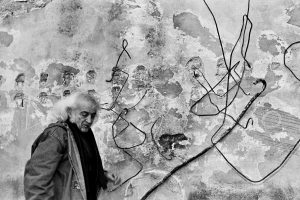

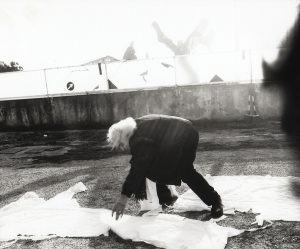

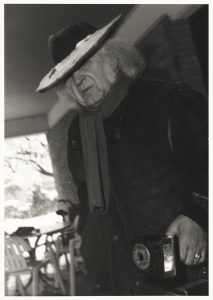

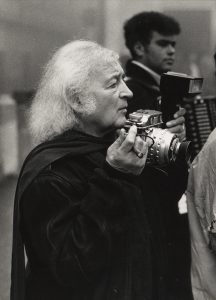

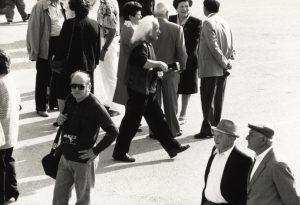

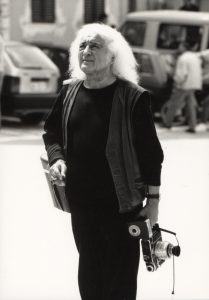

In his later work, Giacomelli took on the role of performer. This performative element was fundamental throughout the course of his practice, the structure of which is highly ritualistic, with repeated gestures assuming symbolic value. Giacomelli’s photographic image is, therefore, far from an instantaneous snap, disconnected from time’s contingency. It assumes and exudes a certain solemnity. The significance with which Giacomelli charges each image enters it into an absolute, atemporal, and thus eternal, realm, in which he sought to immerse himself. Photography is the “pretext” that allows Giacomelli to enter the world. It is as if his whole life led up to the autobiographical focus of his final work, with its fusion of action and speech, life and art.

Giacomelli pro-duces the image, in the etymological sense of the word: he extracts it from the depths of his being in order to render it visible to himself. It is for this reason that Giacomelli considered himself a spectator, part of a precise and ritualistic methodology. It is this dual role of creator-spectator that makes Giacomelli feel so contemporary: he abandoned objectivity in favour of absolute subjectivity, and found himself face to face with his own creativity, as if he were standing before a mirror.

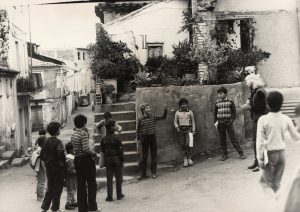

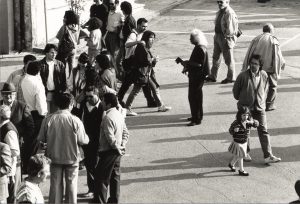

For Giacomelli, photography was not a simple declaration of “this happened in a specific place at a specific time,” as is the case for documentary photography. Instead, his photography absorbs interrelated clusters of subjects and meanings. These clusters are in continual movement (Giacomelli transferred subjects from one print series to another, took photographs of photographs, inserted old photographs into new series, and used superimposition, resulting in images in which present subjects enter scenes from the past). His photographs are in a continual state of change (in his darkroom, Giacomelli altered the textures of reality). The subjects are historically and chronologically unanchored (isolated from their context by Giacomelli’s bitten whites and rendered two-dimensional by his use of daytime flash, a zoom lens, and tight cropping). Giacomelli’s network of images is a continuum of signs and symbols. For Giacomelli, photography was not a tool for testimony. The subjects of his photographs are pure, free-moving signifiers which derive their meaning from being multiplied, repeated, remodelled, and set into new dialogues. This approach aligns Giacomelli’s work with the idea of the Informal in art, and also enables us to trace a method which spans his practice.

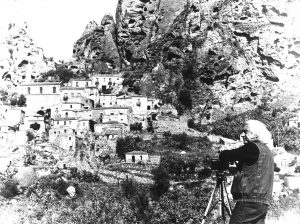

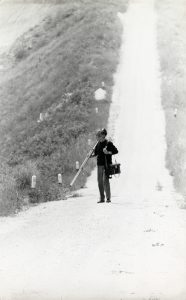

Giacomelli’s creative method allowed him to reset his relationship with this realm of possibility time and again. This is achieved through his systemisation of his whole photographic oeuvre. When Giacomelli finally decided to enter the frame of the photograph, as he did in his later work, using a self-timer, the space is desolate, lifeless, devoid of human subjects, and only inhabited by fake animals and crumbling houses (distilling the notion of subject/signifier to its most essential form). Giacomelli wanted to enact a revitalisation of the inanimate, using fake animals and masks to highlight photography’s ability to animate something that would have otherwise remained inanimate. What does this mean? This means that Giacomelli immerses himself in a “magical” scene (he often defined photography in these terms), which is capable of (symbolically) elapsing every distance, even that between life and death. The inanimate thing gains new life when it assumes its place in the new order of reality mapped out by photography. It is here, in this void of possibility, this realm of infinite potential, that Giacomelli gets closest to the crux of his conception of photography (he defines photography as ‘getting under the skin of reality’): in his final series, he physically enters the space of the photograph, via self-portraiture.

(Katiuscia Biondi in Mario Giacomelli. Sotto la pelle del reale, Ed. 24 Ore Cultura, 2011)

MARIO GIACOMELI: MAKING ART. BEYOND THE LAWS OF THE MARKET.

Giacomelli is unanimously considered a master of photography. In 1955, Paolo Monti declared him ‘photography’s new man.’ In 1964, Giacomelli’s work was acquired by MoMA New York, and today his photographs are found in collections worldwide.

Giacomelli developed his own photographic language: he used high contrast, bitten whites and rich blacks, soft focus, daytime flash, grainy textures and expired photographic materials to create images which are unanchored from reality. His feeling of “joy” when photographing did not derive from realistically capturing an object set before him, but instead from using photography to ‘get under the skin of reality.’ Giacomelli shook off photography’s traditional precepts and used the medium as a means of freely expressing his unconscious. Photography became a space where Giacomelli enacted an introspective ritual, and in doing so immersed himself in the realms of abstraction and poetry. His creative performance lasted his whole lifetime: his photographs are the frames on a film reel which spans the course of his life. The individual images are inextricable from a sense of a whole; they are testament to the intimate relationship between Giacomelli and the world.

Giacomelli’s intellectual lucidity transcended the parameters of traditional intellectualism. He observed aspects of humble daily life with marvel and performed an alchemistic transformation of reality. He used his camera much like an enlarging lens, bringing him in such close contact with reality that looking at the world meant looking at a mirror image of himself.

It was Giacomelli’s almost magical approach, this transformative capacity, which captured the attention of artists, photographers, art critics, gallerists, curators, and scholars, who gathered at his Marchigian Typography in Senigallia (the city he never left).

Giacomelli baulked at the laws and strategies underpinning the art market. He only signed his photographs when they left his archive as entries into exhibitions, fairs, museum donations, or when they were bought by gallerists, who required him to put his signature on them, in which case he signed them on the reverse (rarely on the front). He never specified the number of a print run or the date of single photographs; instead he dated them as series.

It is important to emphasise this aspect of Giacomelli’s practice because it clearly demonstrates his intellectual honesty. This approach to dating and signing his work aligns with his conception of photography: Giacomelli considered his photographic oeuvre as an indivisible whole. Photography was a parallel space in which temporal distinctions (past and present) dissolved, thus excluding any notion of distance or loss. With this as his creative intention, it would have been jarring for him to organise his individual photographs according to numerical categorisation. And yet there is a precise order to his work: the archive is divided into series, with accompanying test prints, negatives, notes, and annotations regarding dates, etc.

Giacomelli’s decision not to annotate his print runs fits with his creative method: for Giacomelli, photographs must be able to be continually revitalised, to be made to ‘breathe again.’ In order for his photographs to inhabit this state of limbo, they cannot be finalised images: this would mean they would exist as purely aesthetic objects to be bought and sold.

Giacomelli took a great deal of care over his photographs, which he treated as pseudo-living organisms (evident in his use of anthropomorphic language when speaking about his work). Giacomelli embedded his photographs in the core matter of each series. He revitalised them over the years by transferring them from one series to the next, entering all of his photographs into dialogue with one another (for further detail on this see Mario Giacomelli. Under the Skin of Reality, ed. Schilt Publishing, 2015).

A photograph is not the product of a mechanical thing, but it is utterly your own, yours because its life continues. The mechanical gesture blocks and freezes, and that’s it, but you’ve got to understand that pressing the shutter doesn’t make anything happen: the real orgasm occurs the moment you choose the image to photograph, and from then on, the image becomes a living, breathing thing, and if you don’t want it to die, you need to develop it in a certain way, and then you need to print it (I don’t even use a thermometer for this because you have to be able to make mistakes, and sometimes the answer lies in the error itself), correct it and modify it, in order to keep it alive. And even when it seems like you’ve finished, it’s never complete. By treating the image in a certain way, everything you did before is reset and it gains new life in a new season.’

(Giacomelli, from his notes on photography, 1990s).

Giacomelli’s photographic oeuvre bears witness to his uninterrupted, fifty-year-long existential journey, charted across the liminal realm that lies between life and art.