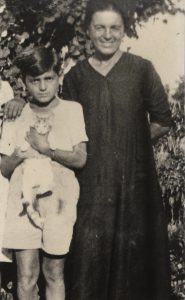

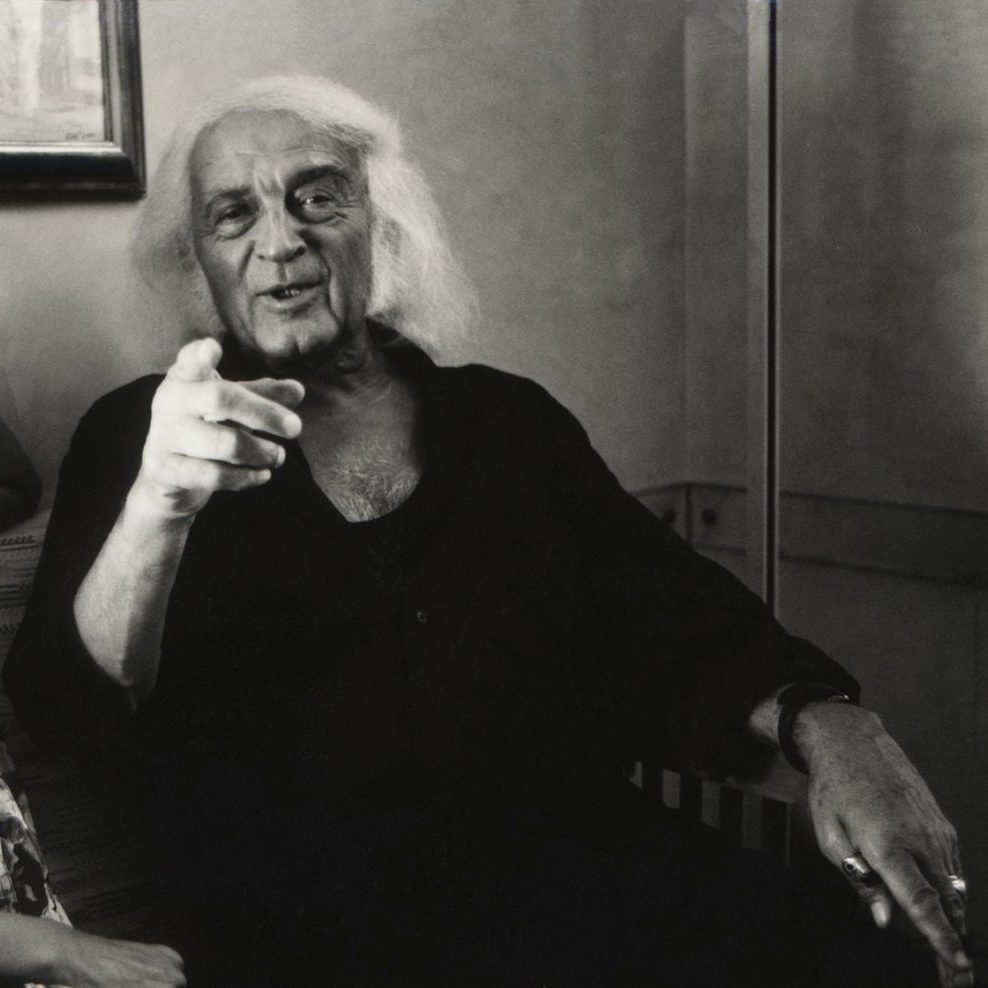

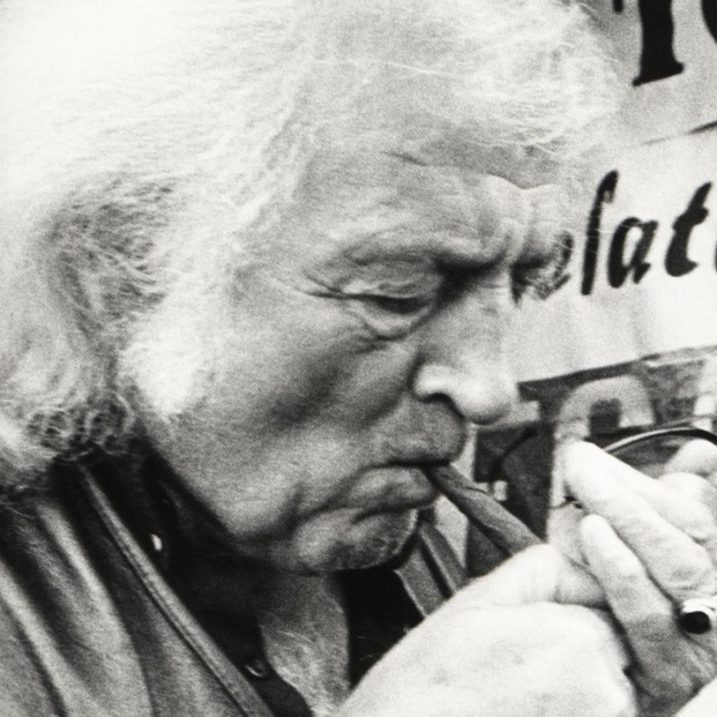

Mario Giacomelli was born in Senigallia on the 1st of August 1925. His father died when he was nine years old, and his mother, a laundress at the hospice in Senigallia, worked hard to provide for her three small children in his absence. Mario was the eldest. At the age of thirteen he began an apprenticeship at the Giunchedi Typography, where he remained until the outbreak of the war. He worked on construction projects to rebuild Senigallia following its wartime bombardment, and then returned to the typography, this time as an employee. In 1950, he decided to open his own typography. He was able to take this plunge thanks to the generosity of one of the elderly residents at the hospice where his mother worked, who lent him the money.

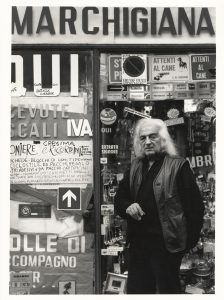

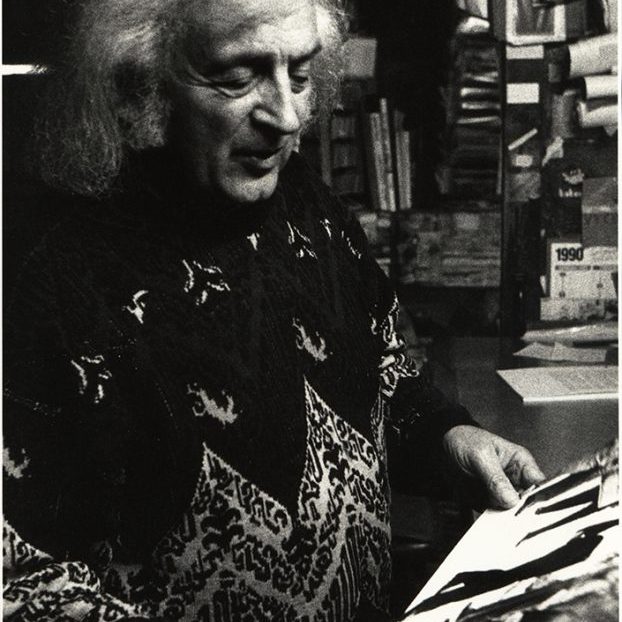

Giacomelli established his Tipografia Marchigiana at 5, Via Mastai. Over the years, it would become a “pilgrimage” destination for artists, critics, scholars and admirers, from all over the world.

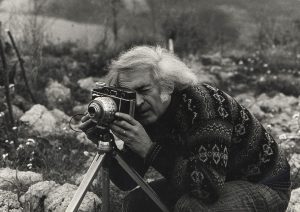

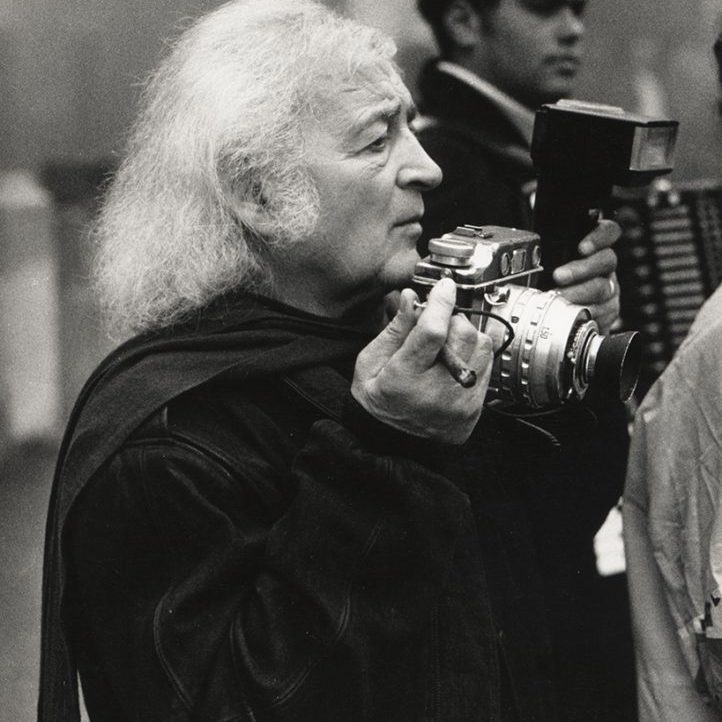

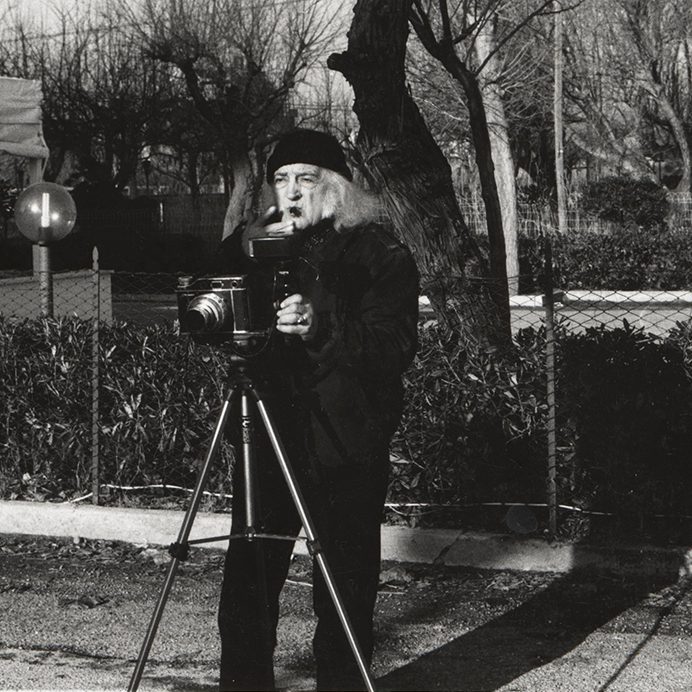

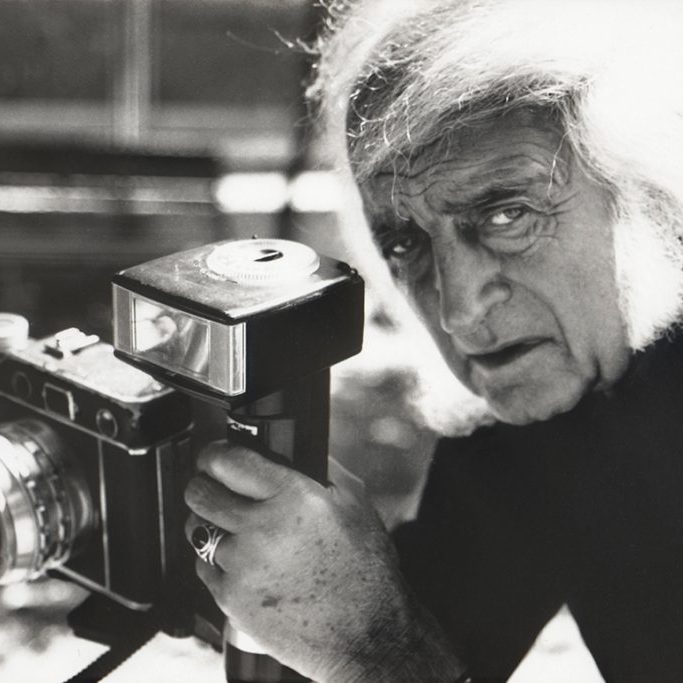

In 1953, Giacomelli bought a Bencini Comet S (CMF) 1950 model, with a retractable achromatic 1:11 lens, 127 film, 1/50+B shutter speed and flash sync. He took his first photographs on the shore in Senigallia.

Amongst these very first photographs was L’approdo (The landing place), an image of a shoe washed up on the tideline, which Giacomelli used to enter various amateur photographic competitions. Giacomelli realised at once that he wanted to express himself via the medium of photography. He began photographing in earnest, making portraits of family members, colleagues and friends, and arranging his subjects in iconographic and theatrical poses. Giacomelli’s famous photograph, Mia Madre (My Mother) (a portrait of his mother holding a spade) is amongst these early works. During this period, Giacomelli visited Torcoletti’s photography workshop. Torcoletti recognised Giacomelli’s extraordinary expressive potential and introduced him to Giuseppe Cavalli, the charismatic artist and critic. Cavalli encouraged Giacomelli to reflect more broadly on photography and art and introduced him to circles of contemporary photographers, such as the groups La Bussola and La Gondola, who were engaging in key discussions about the role of photography in art and in society. With guidance from Ferruccio Ferroni and Cavalli, Giacomelli explored different photographic techniques until he found his own expressive conviction. Misa, a group of local photographers, was formed in 1954. Giacomelli’s path to fame opened up in 1955 when he won the prestigious National Competition in Castelfranco Veneto. Paolo Monti, who sat on the jury for the prize, declared Giacomelli ‘photography’s new man.’

Between 1955-60, Giacomelli photographed a series of still lifes. These black and white photographs were set up in his garden and composed using objects he found about the house: cloth, fruit, bottles, and the like.

Between 1956-60, Giacomelli created a series of Nudes (men and women from his immediate circle). The photographs were not part of an aestheticising meditation on the female body, as Giacomelli explains: ‘[t]he idea of the nude first came to me in the hospice […] When I printed this photo [of the man standing and the woman in the background, both turned away from the camera], I reduced the developing time, leaving it for a shorter period in the acid, which gave it a darker effect. What resulted is another kind of poetry.’ In the 1990s, Giacomelli expanded the series, adding his own nude self-portraits.

Giacomelli soon moved away from the stylistic teachings of Cavalli: he believed Cavalli’s grey tones were insufficient in capturing the intensity and tragedy of life, which he found he was able to convey using stark blacks and whites – almost unsettlingly stark in this initial period. It was at this time that Giacomelli began to explore the potential of the hospice setting and photograph his landscapes. He pursued these subjects for decades to come. Even after having made an international name for himself, Giacomelli continued to enter amateur photography competitions and received numerous prizes and acknowledgements.

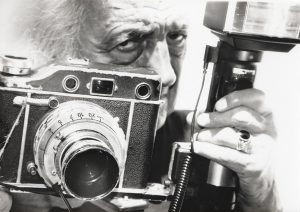

In 1955, Giacomelli’s mythical camera arrived on the scene: a Kobell Press with a Voigtlander colour-heliar 1:3,5/105. This camera never left his side, and he personalised it through a series of adjustments. That same year, Giuseppe Cavalli introduced Giacomelli to Luigi Crocenzi. In 1956, Pietro Donzelli wrote to Giacomelli urging him to structure his photographic production in the form of series and stories. Crocenzi’s advice was the same. Giacomelli’s work from this period is “documentary-esque”: he created the series Lourdes (1957), Scanno (1957 and 1959), Puglia (1958, returning in 1982), Zingari (Gypsies) (1958), Loreto (1959, returning in 1995), Un uomo, una donna, un amore (One man, one woman, one love) (1960/61), Mattatoio(Slaughterhouse) (1960), Pretini (Priests) (1961/63), La buona terra (The good earth) (1964/66).

Meanwhile, Romeo Martinez (one of the 20th century’s leading figures in the art and publishing sector) helped Giacomelli to begin publishing his work in specialised photography journals.

Giacomelli continued to explore the landscape of Le Marche. He began to pay local farmers to use their tractors to furrow patterns and signs in the earth. Giacomelli acted directly on the land prior to photographing it, and then accentuated these markings through his printing process (anticipating the American Land Art movement of the 1960s/70s). Through his explorations of form, Giacomelli saw photography as a means of entering into acutely close contact with reality, allowing it to gain new meaning. This philosophy inspired the series Motivo suggerito dal taglio dell’albero (Motif suggested by the cut of a tree) (1966/68), and similarly Favola, verso possibili significati interiori (A tale, towards possible inner meanings) (1983/84). Giacomelli moved steadily further into abstraction.

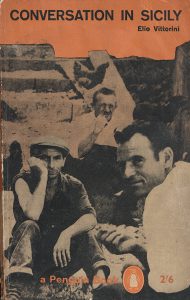

In 1961, Elio Vittorini wrote to Giacomelli, via Luigi Crocenzi, asking him if he could use his image Gente del sud (People of the South) (from the Puglia series) for the cover of the English edition of his book Conversazione in Sicilia (Conversation in Sicily). Two years later, Piero Racanicchi, who, together with Turroni, was one of the first critics to champion Giacomelli’s work, commended his photographs to John Szarkowski, the director of the Department of Photography at MoMA, New York. In 1964, Szarkowski purchased the Scanno series and a selection of images from the series Pretini (Priests).

Giacomelli created the series Verrà la morte e avrà i tuoi occhi (Death will come and will have your eyes) in 1966/68. Over the years, he expanded the series with photographs taken between 1953 and 1983, across different visits to the hospice. This “series” was particularly important to Giacomelli because it allowed him to engage with ideas about death, loneliness, life, longing, and the precipice of life’s disintegration. The series also maintained Giacomelli’s connection with his mother, Libera, who had worked at the hospice as a laundress in order to be able to support her three young children after the premature death of her husband. The series encapsulates Giacomelli’s meditations on time, death, and life.

This practice of compiling a series using photographs from various other series is the crux of Giacomelli’s approach: he elapsed the distance between past and present to create a photographic oeuvre which exists in a continued state of metamorphosis. Echoes reverberate across it. Patterns of destruction and reconstruction play out. It is a living organism.

In 1954/56 Giacomelli created the series Vita d’ospizio (Hospice life). In 1966-68 to make Verrà la morte e avrà i tuoi occhi (Death will come and will have your eyes). In 1981 Ospizio (Hospice), Non fatemi domande (Don’t ask me any questions) andLa zia di Franco (Franco’s aunt). In ’85/87 he composed the series Ninna nanna (Lullaby), inspired by Leonie Adams’ poem. And in 1993 E io ti vidi fanciulla (And I saw you as a girl).

From the 1960s to the mid-1990s, Giacomelli created a series of colour photographs (Landscapes, Still lifes, Abstractions, At the quay). In the context of his large oeuvre of black and white work, these experimental colour photographs are few and far between.

Influenced by Crocenzi, in 1967, Giacomelli set about creating a photographic series structured as a story. He began to explore the poem Caroline Branson from Edgar Lee Masters’ Spoon River Anthology and asked Crocenzi for a plot outline to follow. The series was meant to be broadcast on the television, but Giacomelli found he could not deliver the series in the style Crocenzi wanted it. He completed the series in 1973, having reworked it. It is with this series that Giacomelli began to make use of superimposition, a technique to which he returned time and again.

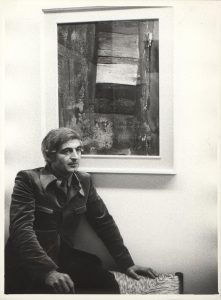

In 1966, Giacomelli met Alberto Burri and they struck up a close friendship. Giacomelli dedicated many of his landscape photographs to Burri. The works recall the mood of the Informal art movement and its visual poetics. The idea of the Informal in art fascinated Giacomelli, so much so that between the 1950s and 1970s he made hundreds of paintings, and in the 1960s he joined a group of artists in Senigallia to explore the relationship between art and abstraction. Painters and sculptors like Marinelli, Ciacci, Donati, Gatti, Genovali, Bonazza, Mandolini, Moroni, and Sabbatini gathered together in Via Arsilli, at Mario Angelini’s framing workshop.

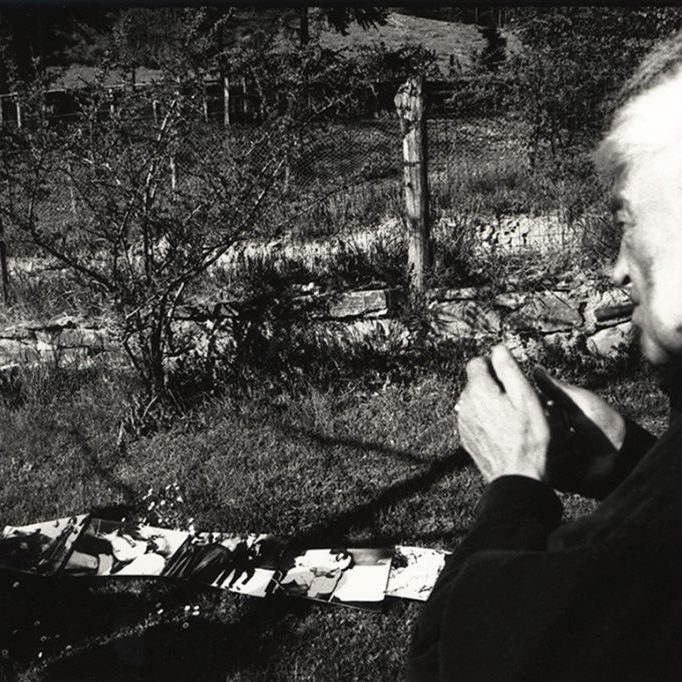

In reality, all of Giacomelli’s practice is, from both a conceptual and methodological perspective, closely linked to the idea of the Informal in art. The first shared notion is that of considering every single element, every individual photograph, not as a finished product, enclosed by ideas of perfection and finitude, but as part of a whole (Giacomelli’s oeuvre). This whole exists in a state of flux, and derives its meaning, shape and vitality, from the interrelation of single elements of which it consists. Giacomelli’s oeuvre is a complex entity; it is an organism which feeds off itself. Giacomelli continually revisited his photographic series to set them in conversation: he established iconographic associations (with symbolic echoes which reverberate across the years), superimposed new photographs over old ones, moved different print variations from one series to another, and created new series using old photographs he had set aside. Per poesie (For poems) (1960s-1990s) is this reserve of images: they are photographs that Giacomelli accumulated and archived specifically for this purpose.

In 1978, Giacomelli’s landscape photographs formed part of the Venice Biennale. In 1980, Arturo Carlo Quintavalle wrote a monograph on Giacomelli (Mario Giacomelli, Feltrinelli, Milan, 1980) and purchased a number of his photographs for the CSAC centre in Parma.

Giacomelli launched himself into abstraction with his series Favola, verso possibili significati interiori (A tale, towards possible inner meanings) (1983-84). It was at this time that Giacomelli met the poet Francesco Permunian, with whom he collaborated to create the series Il teatro della neve (The theatre of snow) (1984-86) and Ho la testa piena mamma (My head is full, Mamma) (1985-87). From this moment on, Giacomelli created photographic series inspired by poetry: he created Il canto dei nuovi emigranti (The song of the new emigrants) (Franco Costabile) (1984-85), Felicità raggiunta si cammina (Happiness is reached, walking) (Eugenio Montale) (1986-92), L’infinito (Infinity) (Giacomo Leopardi) (1986-88), Passato (Past) (Vincenzo Cardarelli) (1986-90), A Silvia (Giacomo Leopardi) (1987-88) (a series which began with under Crocenzi’s guidance in 1964, and then resumed in 1988 with a decidedly more conscious approach to the relationship between poetic text and photographic images), Io sono nessuno (I am nobody) (Emily Dickinson) (1992-94), La notte lava la mente (The night washes the mind) (Mario Luzi) (1994-95), Bando (Call) (Sergio Corazzini) (1997-99), La mia vita intera (My whole life) (Jorge Luis Borges) (1998-2000). He also changed the title of several series: Verrà la morte e avrà i tuoi occhi (Death will come and will have your eyes) (Cesare Pavese) (1954-83), Ninna Nanna (Lullaby) (Leonie Adams) (1985-87), and Io non ho mani che mi accarezzino il volto (There are no hands to caress my face) (Padre David Maria Turoldo).

Between 1983-87, Giacomelli made Il mare dei miei racconti (The sea of my memories), which consists of aerial photographs of the Adriatic coast near Senigallia. Throughout his life, Giacomelli always returned to photograph the sea and the beach. It was, after all, on the shoreline that he took his very first photograph, L’approdo (The landing place). Giacomelli’s practice came full circle: his last series La domenica prima (The Sunday before) was taken on the beach. So too were the photographs taken throughout the summers of the 1960s, Il mare (The sea) (1960s-90s), and all the photographs taken between the 1970s and 1990s, which Giacomelli used to compile Le mie Marche (My Marche) (taken at Marina di Montemarciano), Al molo (At the quay) (in Senigallia), Marotta il mare (The sea at Marotta), Il mare di Fano (The sea at Fano), Storie di mare (Stories of the sea) (taken on the beach in Senigallia), La Rotonda (The terrace) (taken on the beachfront in Senigallia).

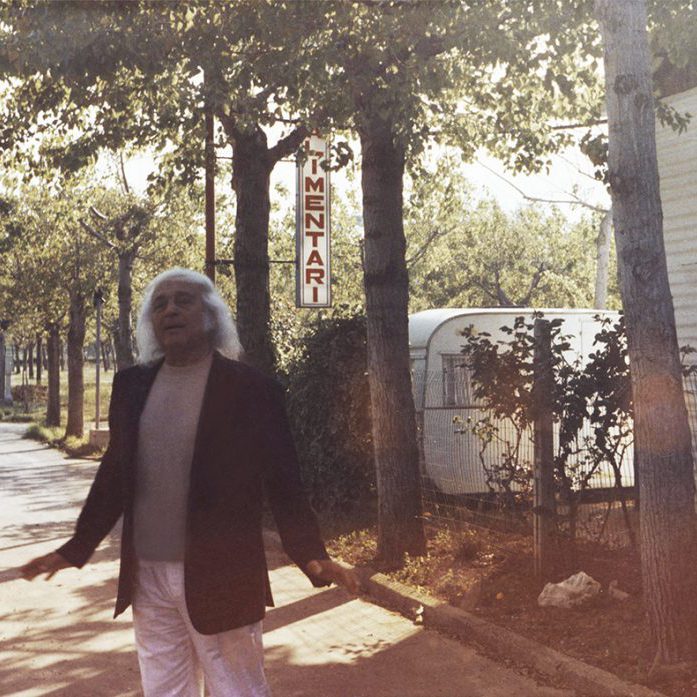

In 1986, Giacomelli’s mother died. The loss caused him great trauma, and it signalled a shift in his photographic practice towards a more explicitly autobiographical approach. By this stage, he had gained international renown and his work was being collected by the most prestigious museums. Yet his practice was becoming increasingly introspective and intimate. He plumbed the depth of his being and fixated on the Marchigian landscape as a means of refinding himself. The series Vita del pittore Bastari (1992-93), Autoritratti (Self-portraits) (1980s-90s), the poetic “abstractions” of Bando (1997-99), 31 Dicembre (31st December) (1997) are scenarios constructed by Giacomelli. The photographs are like frames from a film reel spanning Giacomelli’s whole life.

In this latter period, Giacomelli returned time and again to specific locations dotted about Senigallia’s surrounding hills. Giacomelli’s photographs of these places are reference points which map out an intimate journey through his interiority. Together, these fragments constitute Giacomelli’s belief that photography can give life to the experiences which exist beyond the alienation of daily life, and enter us into a purely phantasmagoric realm of being. It is here that Giacomelli sought to find himself. This approach gave rise to a set of intimate and profoundly autobiographical photographs. The Mario Giacomelli Archive conserves: Bucci, Otello, Cremonini, Polverari, Ferri (Per poesie) (the titles originate from the names of the farmhouses and regions where he set up the scenes to photograph). I ricordi di un ragazzo del ‘25 (The memories of a boy from ‘25) (1999) similarly emerged from this introspective mood, becoming Questo ricordo lo vorrei raccontare (I’d like to tell you about this memory) in 2000. (the title expresses Giacomelli’s vision of photography as a means of triumphing over death). As did Ritorno (Return) (1999/2000) and Così come la morte (Just like death) (1999), a series inspired by Giorgio Caproni’s poem.

In the 1990s, Giacomelli’s restless desire to find poetry in life, and for life, pushed him to venture into abstract space with Territorio del linguaggio (Territory of language) (1994), Astratte (Abstractions) (1990s), Polverari, and Bando (1997-99).

It is interesting to trace the course of Giacomelli’s existential journeying across his photographic practice. Life and art fuse in his vision of photography as a means of getting under the skin of reality, and a means of acknowledging that it is impossible to establish a clear sense of distance between the world and the subject looking at it.

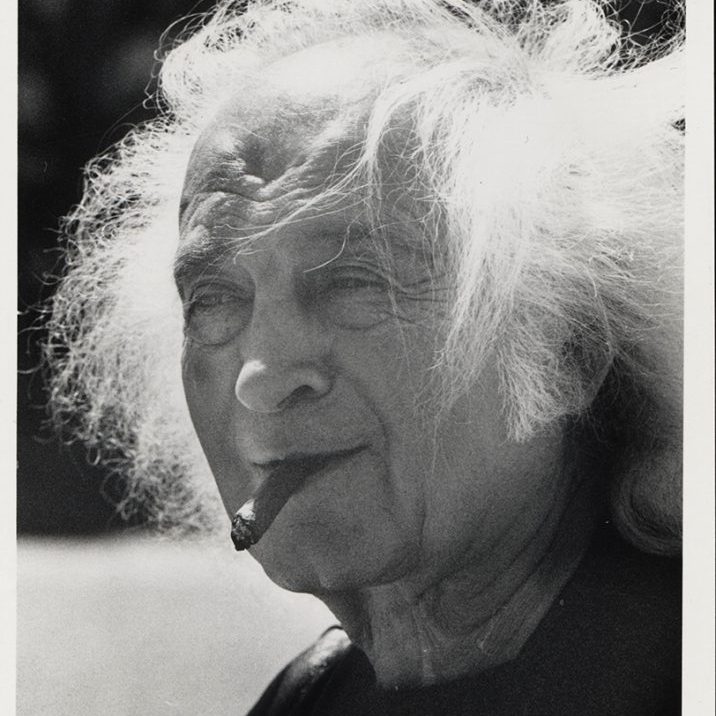

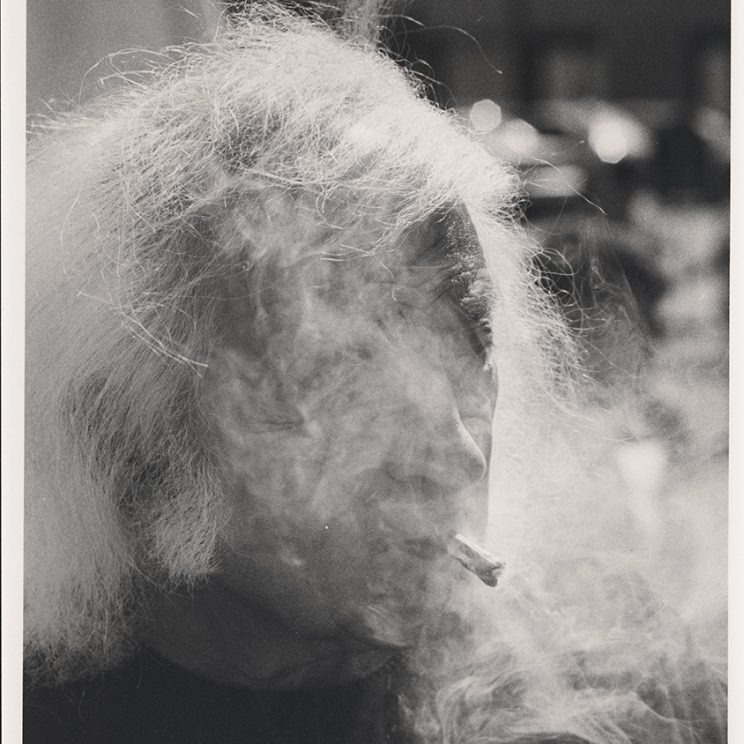

Mario Giacomelli died on the 25th of November 2000, after a year of illness. He worked right up to the last moment to create the series Questo ricordo lo vorrei raccontare (I’d like to tell you about this memory) (2000) and La domenica prima (The Sunday before) (2000).

Throughout his life, Giaomelli never ceased to photograph the fields and hills around Senigallia. These places were as familiar to Giacomelli as his reflection in the mirror. The landscape of Senigallia figures in many series: nestled in the crease of the hill and with his gaze tilted upwards, he photographed his series Paesaggi (Landscapes) (from 1954-60s), which is nostalgic and poetic in tone; Memorie di una realtà (Memories of a reality) (1956-68) features the rectangular farmhouse set into the hillside (in San Silvestro, a province of Senigallia) and was likewise photographed from below; Metamorfosi della terra(Metamorphosis of the land) (1955-68) consists of photographs which were mostly taken on the hills around Arcevia (a hamlet between Senigallia and Sassoferrato), Sant’Angelo (a province of Senigallia), Montelago (a province of Senigallia), and Vallone (a province of Senigallia) (from 1960-80), with the landscape photographed from the opposite hillside, making the land look like it is taking to the sky like a bird. From here on in, Giacomelli began to seek out signs and markings in the land, and used contrast and over-exposure to create rich black areas which decontextualise and abstract the landscape, giving it a cosmic magnitude. The photographs of the square farmhouse also belong to this series. They were taken from a hilltop, across the seasons, years, and at different stages of cultivation. In Storie di terra (o La terre che muore) (Stories of the land or The dying land) (1956-80), a farmhouse is positioned in the centre of the photographs, set amidst cultivated fields. The varying crop patterns are evidence of the land’s morphology; its transformation with the evolution of agricultural technique. The house remains the same while everything else around it changes and veers towards self-destruction: in his photographs from the 1950s and 1960s, we find sheaves of wheat and similar crops, which create the kind of geometric patterns and signs that Giacomelli sought, but these methods of cultivation gradually faded to non-existence as the years passed. At the end of the 1960s, but largely in the 1970s-80s, the land began to degenerate. The photographs from these years expose the furrows and gashes cut into the land by intensive agricultural methods. They bear testament to the destruction of the farmer’s close relationship with the land. For his series Paesaggi dall’alto (Landscapes from above), Giacomelli photographed the land from a new, elevated perspective: this idea came to him in 1975, whilst on a flight to Bilbao, where he had been asked to sit on the jury for a photography prize. Presa di coscienza sulla natura (An epiphany about nature) (1976-90s) grew out of this realisation. This is a series of aerial photographs taken from the window of a Piper plane. Giacomelli’s photographs from this period (1976-1980s) are high contrast. Through abstracting and essentialising forms, they emphasise the importance of signs. The crux of Giacomelli’s approach is (as we read in his notes for his test prints) retaining the vitality of the material. Giacomelli’s aerial landscapes from the 1990s are less contrasting, with fewer markings. Space feels more homogenous. Our gaze is more detached. Intensive agriculture has irreversibly changed the landscape.